In several of my previous posts, I have discussed methods for obtaining word embeddings, such as SVD, word2vec, or GloVe. In this post, I will abstract a level higher and talk about 4 different methods that have been proposed to get embeddings for sentences.

But first, some of you may ask why do we even need a different method for obtaining sentence vectors. Since sentences are essentially made up of words, it may be reasonable to argue that simply taking the sum or the average of the constituent word vectors should give a decent sentence representation. This is akin to a bag-of-words representation, and hence suffers from the same limitations, i.e.

- It ignores the order of words in the sentence.

- It ignores the sentence semantics completely.

Other word vector based approaches are also similarly constrained. For instance, a weighted average technique again loses word order within the sentence. To remedy this issue, Socher et al. combined the words in the order given by the parse tree of the sentence. While this technique may be suitable for complete sentences, it does not work for phrases or paragraphs.

In an earlier post, I discussed several ways in which sentence representations are obtained as an intermediate step during text classification. Several approaches are used for this purpose, such as character to sentence level feature encoding, parse trees, regional (two-view) embeddings, and so on. However, the limitation with such an “intermediate” representation is that the vectors obtained are not generic in that they are closely tied to the classification objective. As such, vectors obtained through training on one objective may not be extrapolated for other tasks.

In light of this discussion, I will now describe 4 recent methods that have been proposed to obtain general sentence vectors. Note that each of these belongs to either of 2 categories: (i) inter-sentence, wherein the vector of one sentence depends on its surrounding sentences, and (ii) intra-sentence, where a sentence vector only depends on that particular sentence in isolation.

Paragraph Vectors

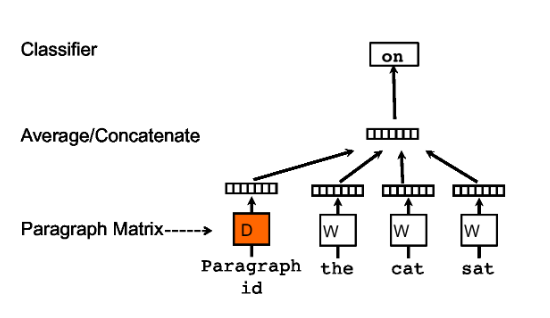

In this ICML’14 paper1 from Mikolov (who also invented word2vec), the authors propose the following solution: a sentence vector can be learned simply by assigning an index to each sentence, and then treating the index like any other word. This is shown in the following figure.

Essentially, every paragraph (or sentence) is mapped to a unique vector, and the combined paragraph and word vectors are used to predict the next word. Through such a training, the paragraph vectors may start storing missing information, thus acting like a memory for the paragraph. For this reason, this method is called the Distributed Memory model (PV-DM).

To obtain the embeddings for an unknown sentence, an inference step needs to be performed. A new column of randomly initialized values is added to the sentence embedding matrix. The inference step is performed keeping all the other parameters fixed to obtain the required vector.

The PV-DM model requires a large amount of storage space since the paragraph vectors are concatenated with all the vectors in the context window at every training step. To solve this, the authors propose another model, called the Distributed BOW (PV-DBOW), which predicts random words in the context window. The downside is that this model does not use word order, and hence performs worse than PV-DM.

Skip-thoughts

While PV was an intra-sentence model, skip-thoughts2 is inter-sentence. The method uses continuity of text to predict the next sentence from the given sentence. This also solves the problem of the inference step that is present in the PV model. If you have read about the skip-gram algorithm in word2vec, skip-thoughts is essentially the same technique abstracted to the sentence level.

In the paper, the authors propose an encoder-decoder framework for training, with an RNN used for both encoding and decoding. In addition to a sentence embedding matrix, this method also generates vectors for the words in the corpus vocabulary. Finally, the objective function to be maximized is as follows.

\[\sum_t \log P(w_{i+1}^t|w_{i+1}^{< t},\mathbf{h}_i) + \sum_t \log P(w_{i-1}^t|w_{i-1}^{< t},\mathbf{h}_i)\]Here, the indices $i+1$ and $i-1$ represent the next sentence and the previous sentence, respectively. Overall, the function represents the sum of log probabilities of correctly predicting the next sentence and the previous sentence, given the current sentence.

Since word vectors are also precited at training time, a problem may arise at the time of inference if the new sentence contains an OOV word. To solve this, the authors present a simple solution for vocabulary expansion. We assume that any word, even if it is OOV, will definitely come from some vector space (say w2v), such that we have its vector representation in that space. As such, every known word has 2 representations, one in the RNN space and another in the w2v space. We can then identify a linear transformation matrix that transforms w2v space vectors into RNN space vectors, and this matrix may be used to obtain the RNN vectors for OOV words.

FastSent

This model, proposed by Kyunghun Cho3, is also an inter-sentence technique, and is conceptually very similar to skip-thoughts. The only difference is that it uses a BOW representation of the sentence to predict the surrounding sentences, which makes it computationally much more efficient than skip-thoughts. The training hypothesis remains the same, i.e., rich sentence semantics can be inferred from the content of adjacent sentences. Since the details of the method are same as skip-thoughts, I will not repeat them here to avoid redundancy.

Sequential Denoising Autoencoders (SDAE)

This technique was also proposed in the same paper3 as FastSent. However, it is essentially an intra-sentence method wherein the objective is to regenerate a sentence from a noisy version.

In essence, in an SDAE, a high-dimensional input data is corrupted according to some noise function and the model is trained to recover the original data from the corrputed version.

In the paper, the noise function $N$ uses 2 parameters as follows.

- For each word $w$ in the sentence $S$, $N$ deletes it according to some probability $p_0$.

- For each non-overlapping bigram in $S$, $N$ swaps the bigram tokens with probability $p_x$.

These are inspired from the “word dropout” and “debagging” approaches, respectively, which have earlier been studied in some detail.

In the last paper3, the authors have performed detailed empirical evaluations of several sentence vector methods, including all of the above. From this analysis, the following observations can be drawn,

- Task-dependency: Although the methods intend to produce general sentence representations which work well across different tasks, it is found that some methods are more suitable from some tasks due to the inherent algorithm. For instance, skip-thoughts perform well on textual entailment tasks, whereas SDAEs perform much better on paraphrase detection.

- Inter vs. intra: The inter-sentence models generate similar vectors in that their nearest neighbors are those sentences which have shared concepts. In contrast, for the intra-sentence models, these are sentences which have more overlapping words.

- Dependency on word order: Although the widely held view is that word order is critical for sentence vectors, the average score for models which are sensitive to word order was found to be almost equal to those which are not. It was even lower for RNN models in unsupervised objectives, which is indeed surprising. One explanation for this may be that the sentences in the dataset, or the evaluation techniques, are not robust enough so as to sufficiently challenge simple word frequency based techniques.

-

Le, Quoc, and Tomas Mikolov. “Distributed representations of sentences and documents.” International Conference on Machine Learning. 2014. ↩

-

Kiros, Ryan, et al. “Skip-thought vectors.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2015. ↩

-

Hill, Felix, Kyunghyun Cho, and Anna Korhonen. “Learning distributed representations of sentences from unlabelled data.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.03483 (2016). ↩ ↩2 ↩3