Transfer learning is undoubtedly the new (well, relatively anyway) hot thing in deep learning right now. In vision, it has been in practice for some time now, with people using models trained to learn features from the huge ImageNet dataset, and then training it further on smaller data for different tasks. In NLP, though, transfer learning was mostly limited to the use of pretrained word embeddings (which, to be fair, improved baselines significantly). Recently, researchers are moving towards transferring entire models from one task to another, and that is the subject of this post.

Sebastian Ruder (whose biweekly newsletter inspires a lot of my deep learning reading) and Jeremy Howard were perhaps the first to make transfer learning in NLP exciting through their ULMFiT method which surpassed all text classification state-of-the-art. This Monday, OpenAI extended their idea and outperformed SOTAs on several NLP tasks. At NAACL 2018, the Best Paper award was given to the paper introducing ELMo, a new word embedding technique very similar to the idea behind ULMFiT, from researchers at AllenAI and Luke Zettlemoyer’s group at UWash (Seattle).

In this article, I will discuss all of these new work and how they are interrelated. Let’s start with Ruder and Howard’s trend-setting architecture.

Universal Language Model Fine-Tuning for Text Classification

Most datasets for text classification (or any other supervised NLP tasks) are rather small. This makes it very difficult to train deep neural networks, as they would tend to overfit on these small training data and not generalize well in practice.

In computer vision, for a couple of years now, the trend is to pre-train any model on the huge ImageNet corpus. This is much better than a random initialization because the model learns general image features and that learning can then be used in any vision task (say captioning, or detection).

Taking inspiration from this idea, Howard and Ruder propose a bi-LSTM model that is trained on a general language modeling (LM) task and then fine tuned on text classification. This would, in principle, perform well because the model would be able to use its knowledge of the semantics of language acquired from the generative pre-training. Ideally, this transfer can be done from any source task $S$ to a target task $T$. The authors use LM as the source task because:

- it is able to capture long-term dependencies in language

- it effectively incorporates hierarchical relations

- it can help the model learn sentiments

- large data corpus is easily available for LM

Formally, “LM introduces a hypothesis space $H$ that should be useful for many other NLP tasks.”

For the architecture, they use the then SOTA AWD-LSTM (which is, I suppose, a multi-layer bi-LSTM network without attention, but I would urge you to read the details in the paper from Salesforce Research). The model was trained on the WikiText-103 corpus.

Once the generic LM is trained, it can be used as is for multiple classification tasks, with some fine-tuning. For this fine tuning and subsequent classification, the authors propose 3 implementation tricks.

Discriminative fine tuning: Different learning rates are used for different layers during the fine-tuning phase of LM (on the target task). This is done because the layers capture different types of information.

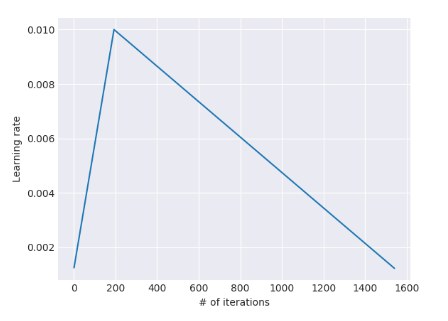

Slanted triangular learning rates (STLR): Learning rates are first increased linearly, and then decreased gradually after a cut, i.e., there is a “short increase” and a “long decay”. This is similar to the aggressive cosine annealing learning strategy that is popular now.

Gradual unfreezing: During the classification training, the LM model is gradually unfreezed starting from the last layer. If all the layers are trained from the beginning, the learning from the LM would be forgotten quickly, and so gradual unfreezing is important to make use of the transfer learning.

On the 6 text classification tasks that they evaluated, there was a relative improvement of 18–24% on the majority of tasks. Further, the following was observed:

- Only 100 labeled samples in classification were sufficient to match the performance of a model trained on 50–100x samples from scratch.

- Pretraining is more useful on small and medium sized data.

- LM quality affects final classification performance.

The analysis in the paper is very thorough, and I would recommend going through it for details, and also to learn how to design experiments for strong empirical results. They suggest some possible future directions as follows:

- The LM pretraining and fine-tuning can be improved.

- The LM can be augmented with other tasks in a multi-task learning setting.

- The pretrained model can be evaluated on tasks other than classification.

- Further analysis can be done to determine what information is captured during pretraining and changed during fine-tuning.

1 and 3 should be noted, in particular, as that makes up the novelty in OpenAI’s new paper discussed below.

Improving Language Modeling by Generative Pre-training

This paper was published on ArXiv this Monday (11 June), and my Twitter feed has been inundated with talk about it since then. Jeremy Howard himself tweeted favorably about it, saying that this was exactly the kind of work he was hoping for in his “future directions”.

This is exactly where we were hoping our ULMFit work would head - really great work from @OpenAI! 😊

— Jeremy Howard (@jeremyphoward) June 11, 2018

If you're doing NLP and haven't tried language model transfer learning yet, then jump in now, because it's a Really Big Deal. https://t.co/0Dj8ChCxvu

What Alec Radford (the first author) does here is

- use a Transformer network (explained below in detail) instead of the AWD-LSTM; and

- evaluate the LM on a variety of NLP tasks, ranging from textual entailment to question-answering.

If you are already aware of the ULMFiT architecture, you only need to know 2 things to understand this paper: (a) how the Transformer works, and (b) how an LM-trained model can be used to evaluate the different NLP tasks.

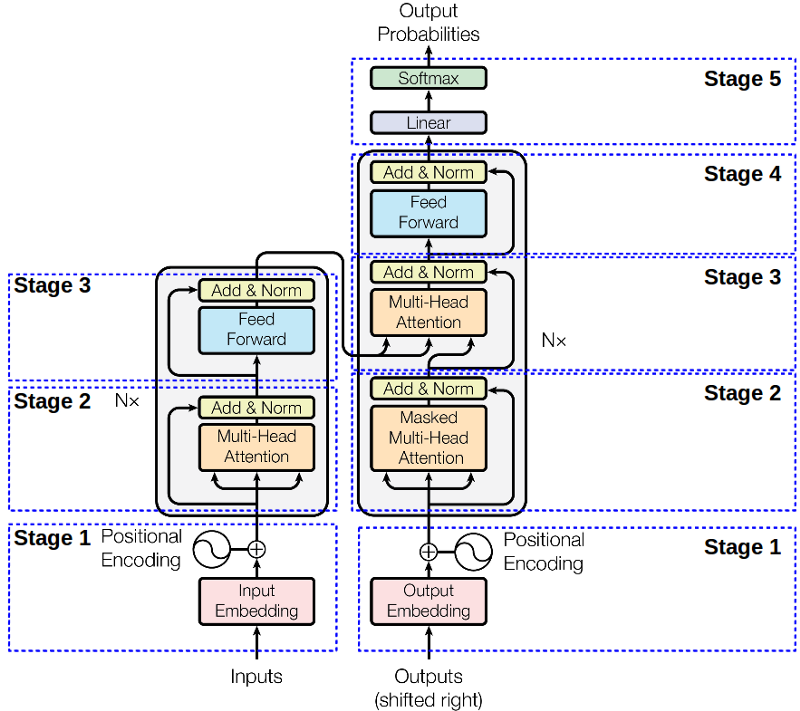

The Transformer

This blog provides an extensive description of the model, originally proposed in this highly popular paper from last year. Here I will go over the salient features. For details, you can go through the linked blog post or the paper itself.

The problem with RNN-based seq2seq models is that since they are sequential models, they cannot be parallelized. One possible solution that was proposed to remedy this involved the use of fully convolutional networks with positional embeddings, but it required O(nlogn) time to relate 2 words at some distance in the sentence. The Transformer solves this problem by completely doing away with convolutions or recurrence, and relying entirely upon self-attention.

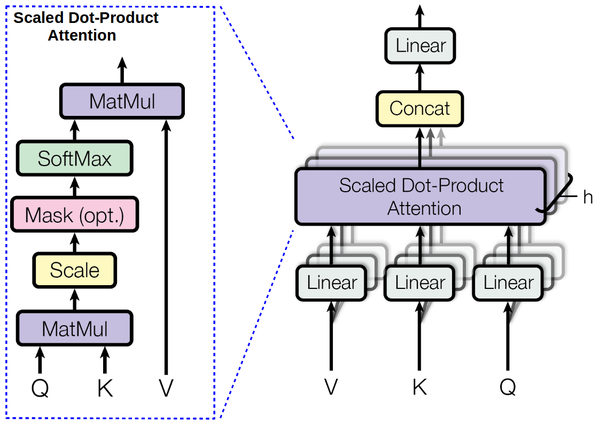

In a simple scalar dot-product attention, weight is computed by taking the dot product of the query (Q) and key (K). The weighted sum of all values V is then the required output. In contrast, in a multihead attention, the input vector itself is divided into chunks and then the scalar dot-product attention is applied on each chunk in parallel. Finally, we compute the average of all the chunk outputs.

The final step consists of a position-wise FFN, which itself is a combination of 2 linear transformations and a ReLU for each position. The following GIF explains this process very effectively.

Transformer

Task-specific input transformations

The second novelty in the OpenAI paper is how they use the pretrained LM model on several NLP tasks.

- Textual entailment: The text (t) and the hypothesis (h) are cocatenated with a $ in between. This makes it naturally suitable for evaluation on an LM model.

- Text similarity: Since the order is not important here, the texts are concatenated in both orders and then processed independently and added element-wise.

- Question-answering and commonsense reasoning: The text, query, and answer option are concatenated with some differentiation symbol in between and each such sample is processed. They are then normalized via softmax to produce output distribution over possible answers.

The authors trained the Transformer LM on the Book Corpus dataset, and improved SOTA on 9 of the 12 tasks. While the results are indeed amazing, the analysis is not as extensive as that performed by Howard and Ruder, probably because the training required a month on 8 GPUs. This was even pointed out by Yoav Goldberg.

Strong empirical results, but I wish there was more focus on a proper comparison / controlled experiments.

— (((λ()(λ() 'yoav)))) (@yoavgo) June 12, 2018

Is the improvement due to LSTM -> Transformer or due to Wiki-1B (single sents) -> BooksCorpus (longer context)? https://t.co/L3WrJW3z12

Deep Contextualized Word Representations

The motivation for this paper, which won the Best Paper award at NAACL’18, is that word embeddings should incorporate both word-level characteristics as well as contextual semantics.

The solution is very simple: instead of taking just the final layer of a deep bi-LSTM language model as the word representation, obtain the vectors of each of the internal functional states of every layer, and combine them in a weighted fashion to get the final embeddings.

The intuition is that the higher level states of the bi-LSTM capture context, while the lower level captures syntax well. This is also shown empirically by comparing the performance of 1st layer and 2nd layer embeddings. While the 1st layer performs better on POS tagging, the 2nd layer achieves better accuracy for a word-sense disambiguation task.

For the initial representation, the authors chose to initialize with the embeddings obtained from a character CNN, so as to have character level morphological information incorporated in the embeddings. Finally for an $L$-layer bi-LSTM, $2L+1$ such vectors need to be combined to get the final representation, after performing some layer normalization.

In the empirical evalutation, the use of ELMo resulted in up to 25% relative increase in performance across several NLP tasks. Moreover, it improves sample efficiency considerably.

(Interestingly, a Google search revealed that this paper was first submitted at ICLR’18 but later withdrawn. I wonder why.)

As Jeremy Howard says, transfer learning is indeed the Next Big Thing in NLP, and these trend-setting papers demonstrate why. I am sure we will see a lot of development in this area in the days to come.