In Part 1 of this two-part series, I discussed some supervised approaches for the objective. In this part, we will look at some unsupervised or semi-supervised approaches, namely a Bayesian model, and transfer learning.

An unsupervised Bayesian model

This paper was published in ACL 20111, back when statistical methods were still being used for NLP tasks. But with the recent forays into generative models, I feel it has again become relevant to understand how such methods worked. The task of frame semantic parsing can be broken down into 3 independent steps:

- Decompose the sentence into lexical items.

- Divide these items into clusters and assign a label to each cluster.

- Predict argument-predicate relations between clusters.

Frames essentially refer to a semantic representation of predicates (such as verbs), and their arguments are represented as clusters. For sake of convenience, we refer both of these structures as semantic classes. For example, in the sentences:

- [India] defeated [England].

- [The Indian team] secured a victory over the [English cricket team].

Here, ‘defeated’ and ‘secured a victory’ both belong to the frame WINNING, while ‘India’ and ‘Indian team’ are grouped into the cluster labeled WINNER.

The authors proposed a generative algorithm which makes use of statistical processes to model semantic parsing. We can summarize the model as follows, for a particular sentence:

- The distribution of semantic classes is given by a hierarchical Pitman-Yor process, i.e.,

- We start with obtaining the semantic class for the root of the tree from the probability distribution which is a sample drawn from the above Pitman-Yor process.

- Once the root is obtained, we call the function GenSemClass on this root.

- Since the current root only has a semantic class, we obtain its syntactic realization from a distribution over all possible syntactic realizations, which is given as a Dirichlet Process with the arguments as the base word and a prior.

- Essentially, the base word $w$ is obtained from a geometric distribution, and the subsequent words are obtained by computing the conditional probability of dependency relation $r$ given $w$, and the next word $p$ given $r$.

- For each argument type $t$, if the probability of having at least 1 argument of type $t$ is non-zero, we generate an argument of that type using function GenArgument, until that probability becomes 0.

- The GenArgument function again computes the base argument from the distribution of syntactic realizations, and then obtains the next semantic class again from the hierarchical PY process.

- We then recursively call the GenSemClass function on this new class.

This is the essence of the algorithm. Basically we get a semantic frame from the PY process, and then generate the corresponding syntax from a Dirichlet process. This is done recursively, hence the need for a hierarchical PY process. For the details of the stochastic processes, you can look at their Wikipedia pages. For the root level parameters, a stick-breaking construction is used, but I am yet to look into the details of this method. However, I suppose this is similar to the broken-stick technique used to estimate the number of eigenvalues to retain in a principal component analysis.

Transfer learning

There were two recent papers in ACL 20172,3 which used some kind of multi-task or transfer learning approach in a neural framework for semantic parsing.

The first of these papers from Markus Dreyer at Amazon uses the popular sequence-to-sequence model developed for machine translation at Google. The sentence is first encoded into an intermediate vector representation using and encoder, and then decoded into an embedding representation for the parse tree. Popular encoders and decoders are stacked bidirectional LSTM layers, usually with some attention mechanism.

Once the parse tree embedding has been obtained, the task remains to generate the actual parse tree. For this, the authors have described a COPY-WRITE mechanism. While reading the output embedding at each step, the model has 2 options:

- COPY: This copies 1 symbol from the input to the output.

- WRITE: This selects one symbol from the vocabulary of all possible outputs.

A final softmax layer generates a probability distribution over both of these choices, such that the probability of choosing WRITE at any step is proportional to an exponential over the output vector at that step, and that for choosing COPY is proportional to an exponential over a non-linear function of the intermediate representation and the output vector (i.e., the encoded and decoded vectors). The authors further describe 3 ways to extend this method in a multi-task setting:

- One-to-many: In this, the encoder is shared but each task has its own decoder and attention parameters.

- One-to-one: The entire sequence is shared, with an added token at the beginning to identify the task.

- One-to-shareMany: This also has a shared encoder and decoder, but the final layer is independent for each task. In this way, a large number of parameters can be shared among tasks while still keeping them sufficiently distinct. Empirically, this model was found to perform best among the three.

The second paper is from Noah Smith’s group at Washington. As with the previous paper, I will first describe the basic model and then explain how it is extended in a multi-task setting.

Given a sentence $x$, and a set of all possible semantic graphs for that sentence $Y(x)$, we want to compute

\[\hat{y} = \text{arg}\min_{y \in Y(x)} S(x,y),~~~~ \text{where } S(x,y) = \sum_{p\in y}s(p),\]i.e., the scoring function $S$ is a sum of local scores, each of which is itself a parametrized function of some local feature. In this paper, these features are taken to be the following 3 constructs (first order logic):

- Predicate

- Unlabeled arc

- Labeled arc

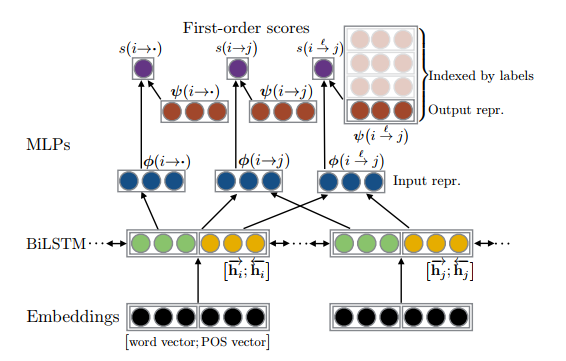

The model is given in the following diagram taken from the paper.

For the 2 input words, we first obtain vectors using a bi-LSTM layer, and these are then fed into multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) corresponding to each of the three local feature constructs mentioned above. Each first-order structure is itself associated with a vector (shown in red). The scoring function $s(p)$ is simply the dot product of the MLPs output and the first-order vector.

The cost function is a max-margin objective with a regularization parameter and a sum over individual losses given as

\[L(x_i,y_i,\theta) = \max_{y\in Y(x_i)} S(x_i,y) + c(y,y_i) - S(x_i,y_i).\]Here, $y_i$ is the gold label output and $y$ is the obtained output, while $c$ is the weighted Hamming distance between the two outputs.

Once this basic architecture is in place, the authors describe 2 method to extend it with transfer learning. The tasks here are 3 different formalisms in semantic dependency parsing (Delph-in MRS, Predicate-Argument Structure, and Prague Semantic Dependencies), so that each of these require a different variation of the output form. In the first method, the representation is shared among all tasks but the scoring is done separately. This further has variants wherein we can either have a single common bi-LSTM for all tasks, or a concatenation of independent and common layers.

The second method describes a joint technique to perform representation and inference learning across all the tasks simultaneously. The description is mathematically involved but intuitively simple, since we are just expressing the inner product in the scoring function in a higher dimension. You can look at the original paper for details and notation.

With this, we come to the end of this series on semantic parsing. Since a lot of models are common between different objectives, these methods are highly relevant across any NLP task, especially with a shift from supervised to unsupervised techniques. While writing this article, I have been thinking of ways of adapting the generative model from the Bayesian paper to a neural architecture, and I might read up more about this in the coming weeks. Till then, keep “learning”!

-

Titov, Ivan, and Alexandre Klementiev. “A Bayesian model for unsupervised semantic parsing.” Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies-Volume 1. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2011. ↩

-

Fan, Xing, et al. “Transfer Learning for Neural Semantic Parsing.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.04326 (2017). ↩

-

Peng, Hao, Sam Thomson, and Noah A. Smith. “Deep Multitask Learning for Semantic Dependency Parsing.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.06855 (2017). ↩