Translation is one of those tasks in language where the arrival of deep learning systems, and in particular sequence-to-sequence, has been something like a boon. In less than 4 years since the first paper on Neural Machine Translation, software giants such as Google and Microsoft have already announced that their translation systems have almost completely shifted from statistical to neural. Gone are the days when researchers mulled over complex word and phrase alignment techniques, and yet fell short on several language combinations. With the latest framework, all you need are a million parallel sentences, and your system can then translate between this pair sufficiently well.

A million parallel sentences — that’s a little constraining, though! It is often difficult and sometimes even impossible to obtain a bilingual parallel corpus for many pairs of languages. In such cases, using a pivot language for triangulation has been found to be helpful. However, even in such supervised systems, the performance is still constrained by the size of the training corpus.

Monolingual data, on the other hand, is available in abundance, and a number of semi-supervised systems do use these, but mostly for the language modeling part of translation. For example, a naive system may perform word-by-word substitution and use a language model trained on the target language to obtain the most probable word order.

Recently, there have been 2 very similar papers (both currently under review at ICLR ’18) which propose to perform completely unsupervised machine translation. In this article, I will discuss both of these papers. A similar blog is available here, but I didn’t know of its existence until I was already halfway through this post.

Unsupervised Neural Machine Translation

This paper1 is from Prof. Kyunghyu Cho (NYU), and the authors have used the traditional seq2seq model with a twist. The encoder is shared across all languages, but each language has its own decoder. The intuition is that a shared encoder will transform a sentence to a shared space representation, from where the language-specific decoder will be able to decode it to its own language.

Both the encoder and decoder are 2 layer bidirectional RNNs with GRU units. Furthermore, the embeddings used in the feature layer are fixed, and are obtained from pre-trained cross-lingual dictionary. This ensures that the shared space representation obtained using the encoder is language-independent.

The paper uses 2 interesting techniques for the unsupervised training.

Denoising: The autoencoder (or seq2seq) is used to reconstruct a sentence in a language, since we only have a monolingual corpus on which to train the system. Due to such a setting, an optimal system would essentially learn to copy the input to the output, and the system would reduce to a word-by-word substitution system. To prevent this, “denoising” is used, which introduces random noise in the input sentence so that copying cannot give the best output. This is dones by making $\frac{N}{2}$ random swaps for any sequence of $N$ tokens. There are 2 advantages to this technique:

- Since copying is out of the picture, the system needs to learn the internal structure of language to perform well.

- By swapping words randomly, we also account for word order divergence across languages. For instance, Los Angeles International Airport in English becomes Aéroport international de Los Angeles in French.

Backtranslation: Even with denoising added, the system is still monolingual. To integrate some element of cross-lingual training, the authors use the method of backtranslation. Given a sentence $x$ in language L1, the shared encoder is used to get the latent representation, and the decoder for the other language L2 is used to obtain a noisy translation $y$. This translation $y$ is then used to predict the original sentence $x$ using the encoder and decoder for L1. This technique creates a pseudo-parallel corpus so that the system can learn cross-lingual translation.

Denoising forces the system to capture broad word-level equivalences, while backtranslation helps it to learn more subtle relations between the language pairs. Furthermore, using pretrained cross-lingual embeddings ensures that the shared latent space representations for sentences in both the languages are near each other when the sentences have the same sense (or meaning).

Unsupervised Machine Translation using Monolingual Corpora Only

A very similar paper2 from researchers at Facebook employs almost the same techniques, but differs slightly in the encoding mechanism. I personally enjoyed reading this paper more than the first one, although they haven’t gone into details of the components they use in their model. The explanation of the loss function for end-to-end training is very lucid, and the overall structuring itself is appealing to a novice researcher like myself.

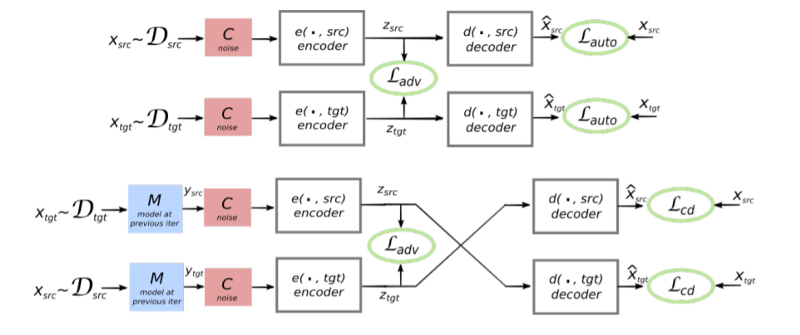

Anyway, the model used in this paper consists of a single encoder and a single decoder (bidirectional LSTM with attention in the decoder, similar to the NMT model used in Google Translate) which is shared by both the languages. For the unsupervised training, 3 techniques are employed.

- Denoising: Similar to the above paper, the autoencoder is denoised so that it does not learn a word-by-word substitution. The noise model in this case consists of: (i) dropping every word with some random probability, and (ii) shuffling the sentence by applying a random permutation.

- Cross-domain training: This is the same as the “backtranslation” technique used in the above paper. However, the authors have explicitly mentioned that to obtain the translation $x$ from the sentence $y$, the model of the previous iteration is used. This requires that the model be initialized with a naive translation strategy, which in this case, is simple word-by-word substitution.

- Adversarial training: In the above paper, due to the use of cross-lingual fixed embeddings in the shared encoder, the latent space representations were arguably similar for similar sentences in different languages. This method does not use cross-lingual embeddings, and hence, the representations will be similar only “as long as the two monolingual corpora exhibit strong structure in feature space.” (Full disclosure: This statement is written as a hand-waving argument without a justification, and one of the reviewers has even pointed this out.) In order to overcome this constraint, the authors employ a discriminator whose task is to predict the language of the encoded sentence. In turn, the encoder has an added term in its loss function which ensures that the representation of similar sentences in different languages are nearby in the latent space.

Since the training is done iteratively and BLEU scores are computed at every step, we can simply select the hyperparameters corresponding to the best performing iteration. Empirically, the authors found that this selection has good correlation with test-time performance of the system. Furthermore, this unsupervised model was found to perform as good as a comparable supervised model trained on 100,000 parallel sentences, which is definitely an encouraging achievement for further research in unsupervised NMT.

-

Artetxe, Mikel, et al. “Unsupervised Neural Machine Translation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.11041 (2017). ↩

-

Lample, Guillaume, Ludovic Denoyer, and Marc’Aurelio Ranzato. “Unsupervised Machine Translation Using Monolingual Corpora Only.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.00043(2017). ↩