While working on my undergrad thesis on relation classification of biomedical text using deep learning methods, I quickly hacked together models in Tensorflow that combined convolutional and recurrent layers in various combinations. While some of these “network architectures” worked superbly (even surpassing state-of-the-art results), I had no clue what was happening inside the model. To gain such an intuition, I read about 20 recent papers on text classification (starting with the first “CNN for sentence classification” paper by Yoon Kim) over the course of a week. Aside from an obvious enlightenment about why my architecture was working the way it was, I also gained valuable insight into how results are presented by experts like Yann LeCunn and Tommi Jaakkola (which would later help me in getting my CoNLL paper accepted as an undergrad).

Anyway, so while reading these myriad of text classification papers, I subconsciously began organizing them under different heads, depending upon the kind of approach used. The common objective across each of these approaches was that they all wanted to model the structural information of the sentence into the sentence embedding. All of this was in March, and ever since, I have wanted to organize the notes I made from my readings into a formal article, so that others may benefit from the insights.

Some background in CNNs and LSTMs is assumed.

Character to sentence level embeddings

Using word vectors (conventionally obtained using Word2Vec or GloVe) has been the most popular technique for input feature embedding. Yann LeCunn proposed character-level embeddings in his NIPS 2015 paper1, and the motivation behind this was that language could also be thought of as a signal similar to speech, with each character representing one bit of information. As such, it was reasonable to encode characters rather than words to obtain sentence level structure more efficiently. Although the proposed method was outperformed even by traditional tf-idf approaches for smaller datasets, the most important hypothesis obtained from empirical analyses was that character level CNNs tend to work well with uncurated user-generated data, such as reviews on Amazon. This makes them especially suitable for use in data wherever misspellings or use of exotic characters is frequent, such as in tweets.

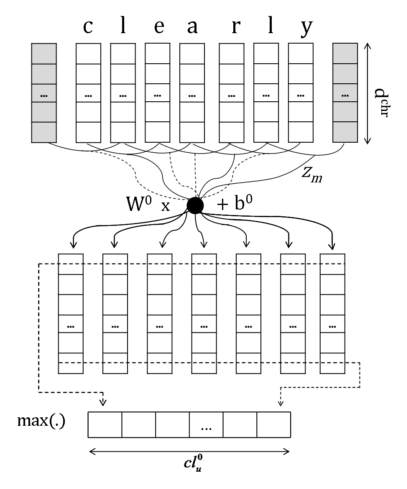

Even before LeCunn’s work, a COLING 2014 paper2 from IBM Research (Brazil) combined embeddings from the character, word, and sentence levels to obtain an amalgamation for the sentence representation. This is done in two convolutional layers as follows:

- In the first layer, vectors are obtained for words using traditional lookup techniques like Word2Vec. At the same time, character-level input vectors corresponding to each word are fed into a convolutional layer and a subsequent max pooling layer, and padding is used so that fixed length outputs are obtained for every word. These convolved features are concatenated with the word-level embeddings to obtain the joint word vector. The rationale behind this is that while word-level embeddings are meant to capture syntactic and semantic information, character-level embeddings capture morphological and shape information.

- The second layer to obtain sentence-level vectors is similar to the character level. On applying convolutions and max pooling, we obtain a global feature representation for the sentence.

Embeddings have become a staple in deep learning models for NLP, and the latest trend is to use deep transfer learning to learn entire parameters for word vectors. While the community has mostly stabilized on using word-level vectors for input features, it wasn’t for lack for exploration, as is evident from these early approaches.

Encoding structural information: parse trees and tensor algebra

Again, for accurate text classification, it is imperative to obtain a good sentence representation that effectively captures the structural information and any semantics possible. If we think about Yoon Kim’s original CNN model in this vein, the limitations in the simple “conv+pool” model becomes obvious. While the convolutional layer helps to recognize short phrases, the final max pooling layer completely disregards any word order or structural information in the sentence. Essentially, we can reorder phrases in the sentences, and the representation would still remain the same.

To solve these problems, a myriad of techniques have been proposed. Here I will discuss 2 of them — the first involves using syntactic parse trees, and the second turns to good old tensor algebra.

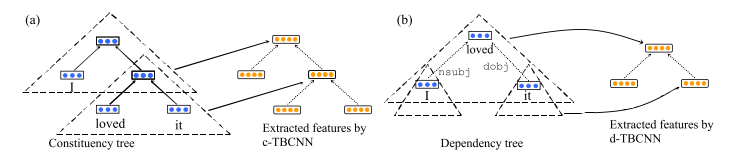

A 2015 paper3 from Peking University proposed two tree-based CNN models, namely c-TBCNN and d-TBCNN, depending on whether constituency or dependency parse trees were used. I will first outline the model:

- A sentence is first converted to a parse tree, and each node is represented as a distributed, real-valued vector. While the nodes of dependency trees are words themselves, those in constituency trees are not. To solve this problem, constituency tree nodes are pretrained using Socher’s RNN and kept fixed thereafter.

- A tree-based convolutional window is defined, which slides over the entire tree to extract structural information of the sentence. The convolutional equation for a window which slides over a parent and its direct children in a constituency tree is given by

- In a dependency tree, a node can have any number of children. To overcome this, weights in these trees are assigned according to dependency type rather than position, and so the convolution formula becomes

In empirical evaluation, d-TBCNN was found to outperform c-TBCNN probably due to d-TBCNN being able to exploit structural features more efficiently because of the compact expressiveness of dependency trees. The paper also provides visualizations for understanding the mechanism of the proposed network, and they show that TBCNNs do integrate information about different words in a window.

A 2015 paper4 from Regina Barzilay and Tommi Jaakkola at MIT used non-linear, non-consecutive convolutions, and turned to tensor algebra to reduce computational complexity. The motivation behind this model is two-fold:

- Conventional CNNs use linear operations on stacked word vectors, which ignores the interesting non-linear interaction between n-grams.

- Consecutive convolutions misses out on the non-consecutive phrases e.g. “not nearly as good” etc.

Essentially, they modified the 2 main components of a CNN-based text classification module, namely window-based convolutions, and the linear convolution operation, with 3 novel modifications.

- Stacked n-gram word vectors are replaced by tensor products, and this n-gram tensor can be seen as a generalization of the typical concatenated vector.

- Since the convolutional filters themselves are high-dimensional tensors (n dimensions corresponding to the size of tensor window, and 1 channel dimension), directly maintaining them as full tensors would lead to parametric explosion. To overcome this, the convolutional tensor is represented using low-rank factorization.

- Instead of applying convolutions only to consecutive n-grams, all possible n-grams are used. At each position, the aggregate representation is the weighted sum of all n-gram representations ending at that position.

The paper makes use of linear algebra very cleverly to extend simple convolution operations across the whole sentence without making it computationally infeasible. In the results section, the authors have also analyzed the importance of such non-linear and non-consecutive activations empirically.

Regional (two-view) embeddings

In a series of papers (published at NIPS 20155 and ICML 20166), Rie Johnson and Tong Zhang introduced the concept of regional embedding in sentences, which was based on two-view embeddings. Essentially, they wanted to answer the question: Can an unlabeled data be used to augment a CNN/LSTM module in a better way than by simply obtaining pretrained word vectors?

In some way, these embeddings are also related to the first section on character to sentence level embeddings. However, I have put it in a separate section since my own network architecture in my CoNLL paper derived hugely from the interpretation given in these papers. (You can say this was when I gained enlightenment!)

In an earlier paper, the authors had showed that using high-dimensional one-hot bag-of-words (BOW) vectors rather than pretrained word vectors proved to be better in simpler systems. Their new objective was to learn regional embeddings from unlabeled data and use it as additional input to the supervised CNN.

But first, what is a tv-embedding? Essentially, it is a function of a view that preserves everything required to predict another view. (See the paper section 2 for details. The motivation for using tv-embeddings is also explained theoretically in the Appendix 5.)

In the papers, the authors used a CNN and an LSTM, respectively, to obtain these tv-embeddings for short regions in the sentences using an unlabeled corpus. They called these as “regional embeddings,” and used them as additional input for the supervised classification task. Furthermore, in their ICML paper, they did away with CNNs entirely, and argued that using bidirectional LSTMs for obtaining the regional embedding and then pooling for the sentence vector gives and adequate sentence representation. However, experimental results showed that using tv-embeddings from networks resulted in the best performing model.

This “regional embedding+pooling” logic was what finally provided the necessary intuition for my own relation classification network.

-

Zhang, Xiang, Junbo Zhao, and Yann LeCun. “Character-level convolutional networks for text classification.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2015. ↩

-

Dos Santos, Cícero Nogueira, and Maira Gatti. “Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentiment Analysis of Short Texts.” COLING. 2014. ↩

-

Mou, Lili, et al. “Discriminative neural sentence modeling by tree-based convolution.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1504.01106 (2015). ↩

-

Lei, Tao, Regina Barzilay, and Tommi Jaakkola. “Molding CNNs for text: non-linear, non-consecutive convolutions.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.04112 (2015). ↩

-

Johnson, Rie, and Tong Zhang. “Semi-supervised convolutional neural networks for text categorization via region embedding.” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

Johnson, Rie, and Tong Zhang. “Supervised and semi-supervised text categorization using LSTM for region embeddings.” International Conference on Machine Learning. 2016. ↩